How Beethoven was brought down by booze and hep B

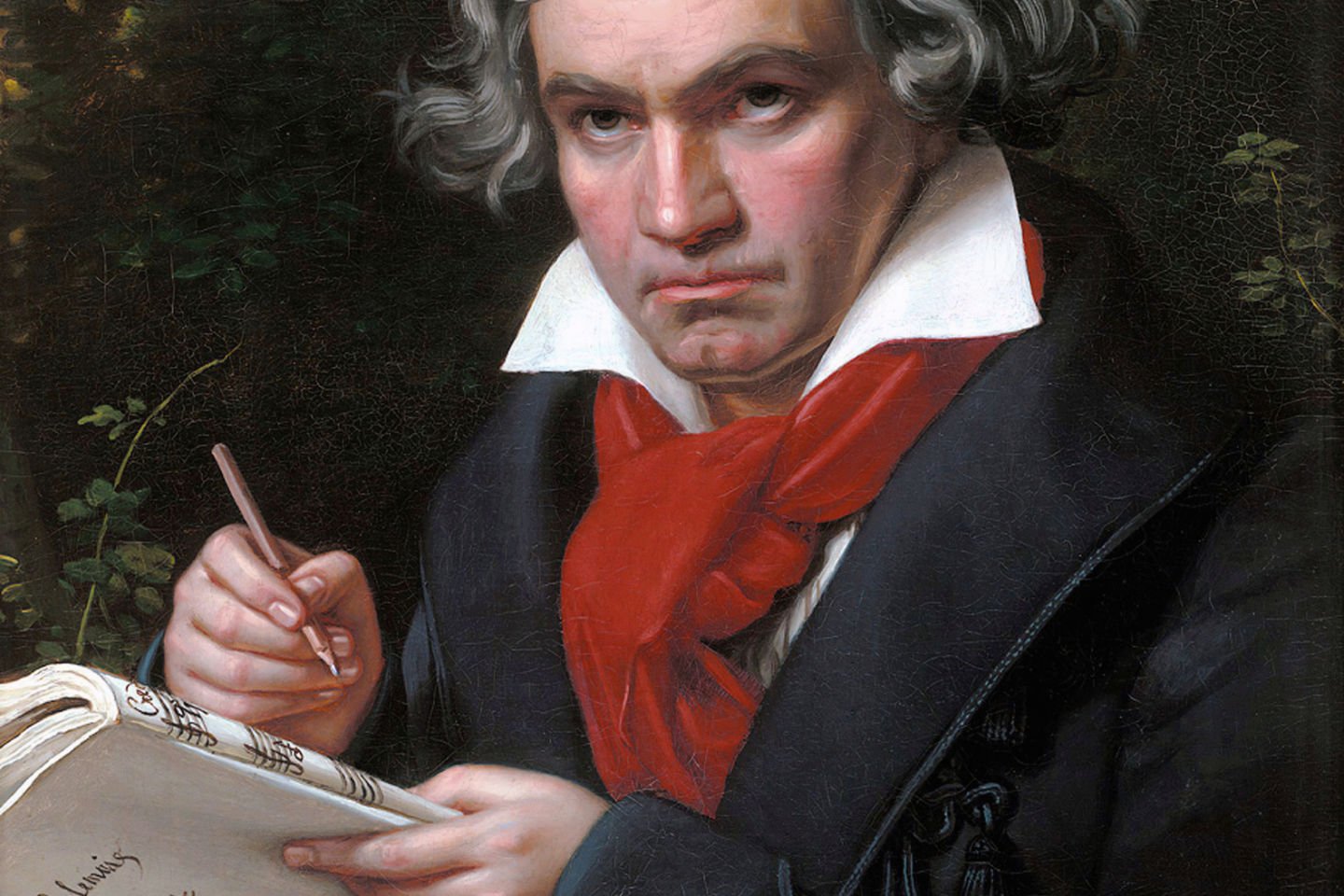

Can the great composer’s crazy hair tell us more than simply that he needed a barber?

Key points

Beethoven died nearly 200 years ago at the age of 56.

Scientists sequenced his genome from his hair.

The study provides new clues about the health complaints that ailed him.

Is this history’s most intriguing cold case?

Beethoven died on 26 March 1827, at just 56, following what researchers now describe as “a wretched existence”.

His loss of hearing while in his 20s is well known, but he was dogged by other health conditions including liver disease. It has been long suspected that he died of lead poisoning.

Famous for his grand and stirring music and composing it while going deaf, Beethoven has long been something of a pin-up boy because of his long, wild and unruly hair.

So, what better way to find out more about the great man’s health than sequencing DNA from a tuft of hair cut from his head while he was on his deathbed?

That’s just what an international team of scientists are doing.

“We have confidently mapped about two-thirds of his genome,” said Tristan Begg, the lead author of a study published in the journal Current Biology and a PhD student at the University of Cambridge.

The researchers sourced the hair from locks he gave to friends while he was alive — a common practice in the 19th century — and several more were cut off when he died.

Throughout life he suffered from debilitating bouts of vomiting and diarrhoea.

While the genome can't tell us exactly what killed him, it reveals he had a genetic predisposition to liver disease and was infected by hepatitis B at some point in his life. He also showed signs of alcoholism.

The researchers did not find any genetic variations associated with early-onset hearing loss. But it appears drinking too much escalated the severity of the liver disease.

Drinking doesn’t help when you also have a genetic vulnerability to hepatitis B.

“When you drink more alcohol, the hepatitis B virus can progress to cirrhosis and maybe even cancer,” one of the researchers said.

“Having one [risk factor] is bad enough, but having two diseases which are damaging the liver faster and further is not good."

So how much did Ludwig imbibe? In one of the conversation books Beethoven used to communicate with his friends after he became totally deaf, there is a reference to him drinking up to a litre of wine every lunch time.

The researchers estimate that if that was true, he was consuming up to 10 Australian standard drinks in each sitting and was probably dependent on alcohol.

Lost sense of smell?

A good sense of smell is linked with slower loss of brain volume and cognitive decline in older people. Scientists in the United States have found a connection between people with pronounced cognitive changes and those who develop cognitive impairment or dementia.

The sense of smell declines with age, and loss of olfactory function (in the organs that help us smell) is also an early symptom of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Future studies may help researchers better understand the potential for using sense of smell as an early indicator of cognitive decline and the role of specific brain regions.

Genetic data from five men living in Belgium with the name "van Beethoven" shared on a commercial ancestry database, may add to the mystery.

Their DNA showed the men were related, and genealogical records showed they were part of Beethoven's family tree, but their Y chromosome did not match Beethoven's.

This suggests that between 1572 and 1700, a male child, potentially Beethoven's father, had been born out of wedlock.

It’s not uncommon these days for people who pursue ancestry testing to find out their father is not their father, or something's not correct in the paternal line.

For his part, Beethoven was a stickler for the truth.

In 1802, he instructed his physician to release details about his diseases after he died. In the end, he outlived his favourite doctor by 18 years.

But, on his deathbed, he told his biographers, “Whatever shall be said of me hereafter shall adhere strictly to the truth in every respect, regardless of who may be hurt, including myself.”

“I hope he's happy with what we did,” researcher Begg said.

Further reading: Current Biology, ABC, NIA

Photo credit: Keith Lance